| linguae |

|

- HOME

-

LATIN & GREEK

-

CIRCULUS LATINUS HONCONGENSIS

>

- ORATIO HARVARDIANA 2007

- NOMEN A SOLEMNIBUS

- CARMINA MEDIAEVALIA

- BACCHIDES

- LATIN & ANCIENT GREEK SPEECH ENGINES

- MARCUS AURELIUS

- ANGELA LEGIONEM INSPICIT

- REGINA ET LEGATUS

- HYACINTHUS

- LATINITAS PONTIFICALIS

- SINA LATINA >

- MONUMENTA CALEDONICA

- HISTORIA HONCONGENSIS

- ARCADIUS AVELLANUS

- LONDINIUM

- ROMAN CALENDAR

- SOMNIUM

- CIRCULUS VOCABULARY

- HESIOD

- CONVENTUS FEBRUARIUS (I)

- CONVENTUS FEBRUARIUS (II)

- CONVENTUS MARTIUS

- CONVENTUS APR 2018

- CONVENTUS APRILIS

- CONVENTUS MAIUS

- CONVENTUS IUNIUS

- CONVENTUS IULIUS

- CONVENTUS SEPT 2017

- CONVENTUS OCT 2017

- CONVENTUS NOV 2017

- CONVENTUS DEC 2017

- CONVENTUS DEC 2017 (II)

- CONVENTUS JAN 2018

- CONVENTUS FEB 2018

- CONVENTUS MAR 2018

- CONVENTUS MAIUS 2018

- CONVENTUS IUN 2018

- CONVENTUS IUL 2018

- CONVENTUS SEPT 2018

- CONVENTUS OCT 2018

- CONVENTUS NOV 2018

- CONVENTUS DEC 2018

- CONVENTUS NATIVITATIS 2018

- CONVENTUS IAN 2019

- CONVENTUS FEB 2019

- CONVENTUS MAR 2019

- CONVENTUS APR 2019

- CONVENTUS MAIUS 2019

- CONVENTUS IUN 2019

- CONVENTUS IULIUS 2019

- CONVENTUS SEP 2019

- CONVENTUS OCT 2019

- CONVENTUS NOV 2019

- CONVENTUS DEC 2019

- CONVENTUS JAN 2020

- CONVENTUS FEB 2020

- CONVENTUS MAR 2020

- CONVENTUS APR 2020

- CONVENTUS IUL 2020

- CONVENTUS SEP 2020 (I)

- CONVENTUS SEPT 2020 (II)

- CONVENTUS OCT 2020

- CONVENTUS NOV 2020

- CONVENTUS IAN 2021

- CONVENTUS IUN 2021

- CONVENTUS IULIUS 2021

- CONVENTUS AUG 2021

- CONVENTUS SEPT 2021

- CONVENTUS OCT 2021

- CONVENTUS NOV 2021

- CONVENTUS FEB 2022 (1)

- CONVENTUS FEB 2022 (2)

- CONVENTUS MAR 2022

- CONVENTUS APRILIS 2022

- CONVENTUS MAIUS 2022

- CONVENTUS IUN 2022

- CONVENTUS IUL 2022

- CONVENTUS SEP 2022

- CONVENTUS OCT 2022

- CONVENTUS NOV 2022

- CONVENTUS DEC 2022

- CONVENTUS IAN 2023

- CONVENTUS FEB 2023

- CONVENTUS MARTIUS 2023

- CONVENTUS APRIL 2023

- CONVENTUS MAIUS 2023

- CONVENTUS IUN 2023

- CONVENTUS IUL 2023

- CONVENTUS SEP 2023

- CONVENTUS OCT 2023

- CONVENTUS IAN 2024

- CONVENTUS MARTIUS (I) 2024

- RES GRAECAE >

-

IN CONCLAVI SCHOLARI

>

- LATIN I

- LATIN I (CAMBRIDGE)

- LATIN II (CAMBRIDGE)

- LATIN II (MON)

- LATIN II (SAT)

- LATIN III (MON)

- LATIN III (SAT)

- LATIN IV (MON)

- LATIN TEENAGERS I

- LATIN TEENAGERS II

- LATIN TEENAGERS III

- LATIN TEENAGERS IV

- LATIN TEENAGERS V

- LATIN TEENAGERS VI

- LATIN TEENAGERS VII

- LATIN TEENAGERS VIII

- LATIN TEENAGERS IX

- LATIN TEENAGERS X

- LATIN TEENAGERS XI

- LATIN SPACE I

- LATIN SPACE II

- LATIN SPACE III

- LATIN SPACE IV

- CARPE DIEM

- INITIUM ET FINIS BELLI

- EPISTULA DE EXPEDITIONE MONTANA

- DE LATINE DICENDI NORMIS >

- ANECDOTA VARIA

- RES HILARES

- CARMINA SACRA

- CORVUS CORAX

- SEGEDUNUM

- VIDES UT ALTA STET NIVE

- USING NUNTII LATINI

- FLASHCARDS

- CARMINA NATIVITATIS

- CONVENTUS LATINITATIS VIVAE >

- CAESAR

- SUETONIUS

- BIBLIA SACRA

- EUTROPIUS

- CICERO

- TACITUS

- AFTER THE BASICS

- AD ALPES

- LIVY

- PLINY

- OVID

- AENEID IV

- AENEID I

- QUAE LATINITAS SIT MODERNA

-

CIRCULUS LATINUS HONCONGENSIS

>

-

NEPALI

- CORRECTIONS TO 'A HISTORY OF NEPAL'

- GLOBAL NEPALIS

- NEPALESE DEMOCRACY

- CHANGE FUSION

- BRIAN HODGSON

- KUSUNDA

- JANG BAHADUR IN EUROPE

- ANCESTORS OF JANG

- SINGHA SHAMSHER

- RAMESH SHRESTHA

- RAMESH SHRESTHA (NEPALI)

- NEPALIS IN HONG KONG

- VSO REMINISCENCES

- BIRGUNJ IMPRESSIONS

- MADHUSUDAN THAKUR

- REVOLUTION IN NEPAL

- NEPAL 1964-2014

- BEING NEPALI

- EARTHQUAKE INTERVIEW

- ARCHIVES IN NEPAL

- FROM THE BEGINNING

- LIMITS OF NATIONALISM

- REST IS HISTORY FOR JOHN WHELPTON

- LIMPIYADHURA AND LIPU LEKH

- BHIMSEN THAPA AWARD LECTURE

- HISTORICAL FICTION

- READING GUIDE TO NEPALESE HISTORY

- LANGUAGES OF THE HIMALAYAS

- REVIEW OF LAWOTI (2007)

- ROMANCE LANGUAGES

-

English

- VIETNAM REFLECTIONS

- GRAMMAR POWERPOINTS

- PHONETICS POWERPOINTS

- MAY IT BE

- VILLAGE IN A MILLION

- ENGLISH RHETORIC

- BALTIC MATTERS

- SHORT STORIES QUESTIONS

- WORD PLAY

- SCOTS

- INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS

- STORY OF NOTTINGHAM

- MEET ME BY THE LIONS

- MNEMONICS

- ALTITUDE

- KREMLIN'S SUICIDAL IMPERIALISM

- CLASSROOM BATTLEFIELD

- MATHEMATICS AND HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS

- OLD TESTAMENT INJUNCTIONS

- KUIRE ORIGINS

- BALTI

- CUBA

- JINNAH AND MODERN PAKISTAN

- ENGLISH IS NOT NORMAL

- HKAS

MARCUS AURELIUS: MEDITATIONS

Bust of Marcus Aurelius in the Glyptothek, Munich

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marcus_Aurelius_Glyptothek_M%C3%BCnchen.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marcus_Aurelius_Glyptothek_M%C3%BCnchen.jpg

This page, which is still under construction, presents the Latin text of the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, Roman emperor from 161 to 180 A.D., together with interlinear English glossing, This collection of philosophical musings and advice to himself was composed by the emperor in Greek, the language in which, like many upper class Romans, he had received much of his education. In 1802, Johann Mattias Schultz published an edition of the work with a commentary discussing textual variants and a Latin translation. Entitled in Latin Marci Antonini Imperatoris Commentariorum Quos Ipse Sibi Scripsit Libri Duodecim (`Twelve Books of Notes Written to himself by the Emperor Marcus Antoninus'), this edition is freely accessible for reading on-line or download in PDF or other formats from the Internet Archive, Google Books or the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek. A slightly modified version of Schultz's translation by Johann Freiderich Dübner was published in 1840 and this was edited and re-published in 2013 by Claude Pavur, whose version of Book 1 is freely available on Academia.edu. The text used for Book 1 in the first of the Word files below is the Dübner-Pavur one, with the correction of one or two typos, but Schultz's original translation, which was located and recommended to me by Clement Ying, is used for Book 2 onwards. The differences between the two versions are not that great but Schultz seems a little more faithful to Marcus Aurelius' Greek.

Both Pavur and Schultz's texts use `j' for consonantal `i' and this feature, typical now for editions of ecclesiastical rather than classical Latin works, has been retained. The texts have been macronised but, as usual, some mistakes with these probably remain. The rough-and-ready recordingas are meant only as assistance to beginners. Restored Pronunciation vis used throughout, even though by the time of Marcus Aurelius some features were different from those of the age of Cicero.

In preparing the English glossing, use has been made of George Long’s 1862 English version, which sticks quite closely to the original and of the 2011 Oxford translation by Robin Hard which is more idiomatic and has an introduction and some useful notes by Christopher Gill. Long's book is freely accessible on Internet Archive and is also included in segmented form with parallel, electronically glossed Greek text in Ira Cleese's edition, available in February 2023 as a Kindle from Amazon for US$9.99. Hard & Gill is currently (November 2022) available on Kindle from Amazon for US$5.99 whilst Gill's own 2013 translation and his expanded notes for Books 1-6 can be freely downloaded from academia.edu. Daniel Robertson has recently published a revised edition of Long's translation but I have not yet seen this nor the translation by Gregory Hays. Long's, Hard's and Hays' translations are compared on Robertson's website.

A.S.L Farquharson's edition of the Greek text with facing English translation and a full introduction, including discussion of the manuscript tradition, was published in 1944 and can be downloaded from Wikimedia. Farquharson's commentary, published as Volume II of his work, is unfortunately not freely available on the web.

Marcus Aurelius's Greek original is often difficult to interpret both because of his own lack of clarity and of copyists' erors. Matters are made even worse by the ambiguity of terms like anima (for Greek πνευμάτιον. pneumation) or spiritus (for Greek ἄνεμος, anemos) which can refer both to air in motion and to the soul. In addition, the published translations from the Greek, whilst helping understand Marcus Aurelius' intended meaning, may not always correspond with what Schultz or Dübner thought he meant. I have tried to note where the Latin seems an inaccurate representation of the Greek but may have missed some instances.

For the Stoic beliefs to which Marcus Aurelius subscribed, there is a brief account in Gill's introduction to the Oxford translation and also in the recent work of Ian Hensley, including `The Foundations of Stoic Physics’ (2021) and `The Physics of Pneuma in Early Stoicism’ (2020). For a popularisation of Stoic teaching on morality, there is the lecture in simple Latin which the authors of Book IV of the Cambridge Latin Course put into the mouth of Euphrosyne, a fictional Athenian philosopher. Outside of North America, this can be freely accessed here, with hyper-linked English glosses for each word. There are also numerous articles on the Internet about the practical advice offered in the Meditations, including how to get out of bed on a cold morning!

In contrast to the enduring popularity of Marcus Aurelius' work and the current vogue for Stoicism, critical voices include Bertrand Russell's section on Stoicism in his History of Western Philosophy and Neil Furrant's recent (February 2023) essay, `3 reasons not to be a Stoic (but try Nietzsche instead)'.

In his public role as emperor, much of Marcus Aurelius' time was sent trying to contain the German tribes on the northern frontier but he is also generally regarded as a conscientious and capable administrator and is conventionally classified as the last of the `Five Good Emperors' who ruled from the death of Domitian in 96 A.D. to the accession of Marcus Aurelius' own son Commodus in 180. We also possess a more intimate portrait of him than of most persons in the Greco-Roman period both because of the self-relevatory nature of Meditations and because of the survival of correspondence with his tutor, Fronto, some of which is added as an appendix to Hard & Gill's book. The primary sources for his reign are quoted extensively in the standard modern account of his life, Anthony Birley's Marcus Aurelius: a Biography (2nd. ed., 1993).

There remain, however, unanswered questions, including whether the emperor was an an opium addict. Thomas Africa suggests this in hs 1961 article `The Opium Addiction of Marcus Aurelius’ , arguing that it was the result of opium contained in the theriac which his physician Galen prescribed and which he took daily. The case is rejected by François P. Retief in his essay `Marcus Aurelius: was he an Opium Addict?’ , on the grounds that the amount calculated by Africa himself was way below critical level and that, even if the dosage had to be increased, it would have needed to be 50-fold to result in addiction. He also notes that long-term addiction brings mental deterioration of which there is no evidence in the emperor's case. Against this, however, it should be remembered that, although opium use does result in neurological damage and eventual respiratory failure. an addict can continue to function adequately for a considerable time providing the opium supply is maintained.

The belief that Marcus was addicted is shared by G.R.Stanton’s in his 1969 Historia article `Marcus Aurelius, Emperor and Philosopher’ He argues that there was no real connection between Stoicism and the emperor actions as ruler and that both philosophy and the drug addiction, were an escape from the pressures of his imperial role. There was undoubtedly an improvement during Marcus’ reign in the legal protection afforded to slaves but, despite Stoicism’s emphasis on slave and free man’s common humanity, Stanton believes this reform was probably not the work of Marcus himself.

Both Pavur and Schultz's texts use `j' for consonantal `i' and this feature, typical now for editions of ecclesiastical rather than classical Latin works, has been retained. The texts have been macronised but, as usual, some mistakes with these probably remain. The rough-and-ready recordingas are meant only as assistance to beginners. Restored Pronunciation vis used throughout, even though by the time of Marcus Aurelius some features were different from those of the age of Cicero.

In preparing the English glossing, use has been made of George Long’s 1862 English version, which sticks quite closely to the original and of the 2011 Oxford translation by Robin Hard which is more idiomatic and has an introduction and some useful notes by Christopher Gill. Long's book is freely accessible on Internet Archive and is also included in segmented form with parallel, electronically glossed Greek text in Ira Cleese's edition, available in February 2023 as a Kindle from Amazon for US$9.99. Hard & Gill is currently (November 2022) available on Kindle from Amazon for US$5.99 whilst Gill's own 2013 translation and his expanded notes for Books 1-6 can be freely downloaded from academia.edu. Daniel Robertson has recently published a revised edition of Long's translation but I have not yet seen this nor the translation by Gregory Hays. Long's, Hard's and Hays' translations are compared on Robertson's website.

A.S.L Farquharson's edition of the Greek text with facing English translation and a full introduction, including discussion of the manuscript tradition, was published in 1944 and can be downloaded from Wikimedia. Farquharson's commentary, published as Volume II of his work, is unfortunately not freely available on the web.

Marcus Aurelius's Greek original is often difficult to interpret both because of his own lack of clarity and of copyists' erors. Matters are made even worse by the ambiguity of terms like anima (for Greek πνευμάτιον. pneumation) or spiritus (for Greek ἄνεμος, anemos) which can refer both to air in motion and to the soul. In addition, the published translations from the Greek, whilst helping understand Marcus Aurelius' intended meaning, may not always correspond with what Schultz or Dübner thought he meant. I have tried to note where the Latin seems an inaccurate representation of the Greek but may have missed some instances.

For the Stoic beliefs to which Marcus Aurelius subscribed, there is a brief account in Gill's introduction to the Oxford translation and also in the recent work of Ian Hensley, including `The Foundations of Stoic Physics’ (2021) and `The Physics of Pneuma in Early Stoicism’ (2020). For a popularisation of Stoic teaching on morality, there is the lecture in simple Latin which the authors of Book IV of the Cambridge Latin Course put into the mouth of Euphrosyne, a fictional Athenian philosopher. Outside of North America, this can be freely accessed here, with hyper-linked English glosses for each word. There are also numerous articles on the Internet about the practical advice offered in the Meditations, including how to get out of bed on a cold morning!

In contrast to the enduring popularity of Marcus Aurelius' work and the current vogue for Stoicism, critical voices include Bertrand Russell's section on Stoicism in his History of Western Philosophy and Neil Furrant's recent (February 2023) essay, `3 reasons not to be a Stoic (but try Nietzsche instead)'.

In his public role as emperor, much of Marcus Aurelius' time was sent trying to contain the German tribes on the northern frontier but he is also generally regarded as a conscientious and capable administrator and is conventionally classified as the last of the `Five Good Emperors' who ruled from the death of Domitian in 96 A.D. to the accession of Marcus Aurelius' own son Commodus in 180. We also possess a more intimate portrait of him than of most persons in the Greco-Roman period both because of the self-relevatory nature of Meditations and because of the survival of correspondence with his tutor, Fronto, some of which is added as an appendix to Hard & Gill's book. The primary sources for his reign are quoted extensively in the standard modern account of his life, Anthony Birley's Marcus Aurelius: a Biography (2nd. ed., 1993).

There remain, however, unanswered questions, including whether the emperor was an an opium addict. Thomas Africa suggests this in hs 1961 article `The Opium Addiction of Marcus Aurelius’ , arguing that it was the result of opium contained in the theriac which his physician Galen prescribed and which he took daily. The case is rejected by François P. Retief in his essay `Marcus Aurelius: was he an Opium Addict?’ , on the grounds that the amount calculated by Africa himself was way below critical level and that, even if the dosage had to be increased, it would have needed to be 50-fold to result in addiction. He also notes that long-term addiction brings mental deterioration of which there is no evidence in the emperor's case. Against this, however, it should be remembered that, although opium use does result in neurological damage and eventual respiratory failure. an addict can continue to function adequately for a considerable time providing the opium supply is maintained.

The belief that Marcus was addicted is shared by G.R.Stanton’s in his 1969 Historia article `Marcus Aurelius, Emperor and Philosopher’ He argues that there was no real connection between Stoicism and the emperor actions as ruler and that both philosophy and the drug addiction, were an escape from the pressures of his imperial role. There was undoubtedly an improvement during Marcus’ reign in the legal protection afforded to slaves but, despite Stoicism’s emphasis on slave and free man’s common humanity, Stanton believes this reform was probably not the work of Marcus himself.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NOTE: The recordings above are rough and ready ones meant only as a general aid to reading aloud. They follow the conventional reconstruction of pronunciation in the age of Cicero, even though by Marcus Aurelius's time there had been a number of changes, including the shift in the sound represented by `ae' from the diphthong in English `high' to the simple vowel in `bed'.

Rome's Danube Frontier in the 2nd. century A.D. showing at the top the location of the Quadi, in whose territory some of the Meditations was composed.

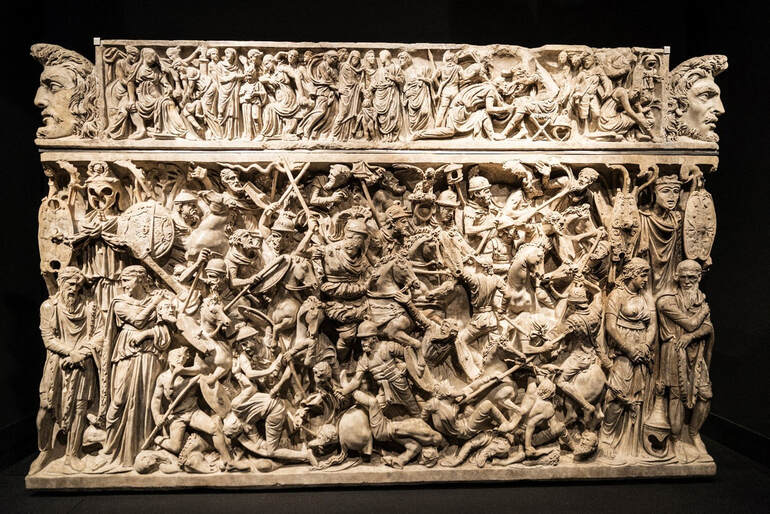

The Portonaccio sarcophagus, dating from the 2nd-century and probably made for a general killed in Marcus Aurelius' 172–175 AD campaign

Finally, on a lighter note, one enthusiast for Marcus Aurelius and Stoicism has made the emperor a character in a series of activity books for young children, one of which is set in Hong Kong.