| linguae |

|

- HOME

-

LATIN & GREEK

-

CIRCULUS LATINUS HONCONGENSIS

>

- ORATIO HARVARDIANA 2007

- NOMEN A SOLEMNIBUS

- CARMINA MEDIAEVALIA

- BACCHIDES

- LATIN & ANCIENT GREEK SPEECH ENGINES

- MARCUS AURELIUS

- ANGELA LEGIONEM INSPICIT

- REGINA ET LEGATUS

- HYACINTHUS

- LATINITAS PONTIFICALIS

- SINA LATINA >

- MONUMENTA CALEDONICA

- HISTORIA HONCONGENSIS

- ARCADIUS AVELLANUS

- LONDINIUM

- ROMAN CALENDAR

- SOMNIUM

- CIRCULUS VOCABULARY

- HESIOD

- CONVENTUS FEBRUARIUS (I)

- CONVENTUS FEBRUARIUS (II)

- CONVENTUS MARTIUS

- CONVENTUS APR 2018

- CONVENTUS APRILIS

- CONVENTUS MAIUS

- CONVENTUS IUNIUS

- CONVENTUS IULIUS

- CONVENTUS SEPT 2017

- CONVENTUS OCT 2017

- CONVENTUS NOV 2017

- CONVENTUS DEC 2017

- CONVENTUS DEC 2017 (II)

- CONVENTUS JAN 2018

- CONVENTUS FEB 2018

- CONVENTUS MAR 2018

- CONVENTUS MAIUS 2018

- CONVENTUS IUN 2018

- CONVENTUS IUL 2018

- CONVENTUS SEPT 2018

- CONVENTUS OCT 2018

- CONVENTUS NOV 2018

- CONVENTUS DEC 2018

- CONVENTUS NATIVITATIS 2018

- CONVENTUS IAN 2019

- CONVENTUS FEB 2019

- CONVENTUS MAR 2019

- CONVENTUS APR 2019

- CONVENTUS MAIUS 2019

- CONVENTUS IUN 2019

- CONVENTUS IULIUS 2019

- CONVENTUS SEP 2019

- CONVENTUS OCT 2019

- CONVENTUS NOV 2019

- CONVENTUS DEC 2019

- CONVENTUS JAN 2020

- CONVENTUS FEB 2020

- CONVENTUS MAR 2020

- CONVENTUS APR 2020

- CONVENTUS IUL 2020

- CONVENTUS SEP 2020 (I)

- CONVENTUS SEPT 2020 (II)

- CONVENTUS OCT 2020

- CONVENTUS NOV 2020

- CONVENTUS IAN 2021

- CONVENTUS IUN 2021

- CONVENTUS IULIUS 2021

- CONVENTUS AUG 2021

- CONVENTUS SEPT 2021

- CONVENTUS OCT 2021

- CONVENTUS NOV 2021

- CONVENTUS FEB 2022 (1)

- CONVENTUS FEB 2022 (2)

- CONVENTUS MAR 2022

- CONVENTUS APRILIS 2022

- CONVENTUS MAIUS 2022

- CONVENTUS IUN 2022

- CONVENTUS IUL 2022

- CONVENTUS SEP 2022

- CONVENTUS OCT 2022

- CONVENTUS NOV 2022

- CONVENTUS DEC 2022

- CONVENTUS IAN 2023

- CONVENTUS FEB 2023

- CONVENTUS MARTIUS 2023

- CONVENTUS APRIL 2023

- CONVENTUS MAIUS 2023

- CONVENTUS IUN 2023

- CONVENTUS IUL 2023

- CONVENTUS SEP 2023

- CONVENTUS OCT 2023

- CONVENTUS IAN 2024

- CONVENTUS MARTIUS (I) 2024

- RES GRAECAE >

-

IN CONCLAVI SCHOLARI

>

- LATIN I

- LATIN I (CAMBRIDGE)

- LATIN II (CAMBRIDGE)

- LATIN II (MON)

- LATIN II (SAT)

- LATIN III (MON)

- LATIN III (SAT)

- LATIN IV

- LATIN TEENAGERS I

- LATIN TEENAGERS II

- LATIN TEENAGERS III

- LATIN TEENAGERS IV

- LATIN TEENAGERS V

- LATIN TEENAGERS VI

- LATIN TEENAGERS VII

- LATIN TEENAGERS VIII

- LATIN TEENAGERS IX

- LATIN TEENAGERS X

- LATIN TEENAGERS XI

- LATIN SPACE I

- LATIN SPACE II

- LATIN SPACE III

- LATIN SPACE IV

- CARPE DIEM

- INITIUM ET FINIS BELLI

- EPISTULA DE EXPEDITIONE MONTANA

- DE LATINE DICENDI NORMIS >

- ANECDOTA VARIA

- RES HILARES

- CARMINA SACRA

- CORVUS CORAX

- SEGEDUNUM

- VIDES UT ALTA STET NIVE

- USING NUNTII LATINI

- FLASHCARDS

- CARMINA NATIVITATIS

- CONVENTUS LATINITATIS VIVAE >

- CAESAR

- SUETONIUS

- BIBLIA SACRA

- EUTROPIUS

- CICERO

- TACITUS

- AFTER THE BASICS

- AD ALPES

- LIVY

- PLINY

- OVID

- AENEID IV

- AENEID I

- QUAE LATINITAS SIT MODERNA

-

CIRCULUS LATINUS HONCONGENSIS

>

-

NEPALI

- CORRECTIONS TO 'A HISTORY OF NEPAL'

- GLOBAL NEPALIS

- NEPALESE DEMOCRACY

- CHANGE FUSION

- BRIAN HODGSON

- KUSUNDA

- JANG BAHADUR IN EUROPE

- ANCESTORS OF JANG

- SINGHA SHAMSHER

- RAMESH SHRESTHA

- RAMESH SHRESTHA (NEPALI)

- NEPALIS IN HONG KONG

- VSO REMINISCENCES

- BIRGUNJ IMPRESSIONS

- MADHUSUDAN THAKUR

- REVOLUTION IN NEPAL

- NEPAL 1964-2014

- BEING NEPALI

- EARTHQUAKE INTERVIEW

- ARCHIVES IN NEPAL

- FROM THE BEGINNING

- LIMITS OF NATIONALISM

- REST IS HISTORY FOR JOHN WHELPTON

- LIMPIYADHURA AND LIPU LEKH

- BHIMSEN THAPA AWARD LECTURE

- HISTORICAL FICTION

- READING GUIDE TO NEPALESE HISTORY

- LANGUAGES OF THE HIMALAYAS

- REVIEW OF LAWOTI (2007)

- ROMANCE LANGUAGES

-

English

- VIETNAM REFLECTIONS

- GRAMMAR POWERPOINTS

- PHONETICS POWERPOINTS

- MAY IT BE

- VILLAGE IN A MILLION

- ENGLISH RHETORIC

- BALTIC MATTERS

- SHORT STORIES QUESTIONS

- WORD PLAY

- SCOTS

- INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS

- STORY OF NOTTINGHAM

- MEET ME BY THE LIONS

- MNEMONICS

- ALTITUDE

- KREMLIN'S SUICIDAL IMPERIALISM

- CLASSROOM BATTLEFIELD

- MATHEMATICS AND HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS

- OLD TESTAMENT INJUNCTIONS

- KUIRE ORIGINS

- BALTI

- CUBA

- JINNAH AND MODERN PAKISTAN

- ENGLISH IS NOT NORMAL

- HKAS

CIRCULUS LATINUS HONCONGENSIS

香港拉丁文協會

Circulus Annum Caprinum (羊年, Year of the Goat) in Campo Picto (錦田, Kam Tin) celebrat

Conventus proximus hora septima et dimidia (7.30) die Veneris 26a Ianuarii (26/1/24) in caupona Basmati habebitur ut de medio capitulo 32 (Et cum interdixisset ..) usque ad finem capituli 35 in Vita Neronis a Suetonio composita recitemus. Descriptionem operum Suetonii et textum versione Anglica interlineari , commentariis et picturis instructum apud https://linguae.weebly.com/suetonius.html invenies. Necesse est documentum c.t. suetonius_nero_26-47_.doc depromere. Si voles adesse, ad diem 24, quaeso, Iohannem Velptonium per epistulam electronicam vel per 93696180 certiorem fac.

De rebus in Circulis Latinis agendis et regulis nostris infra et Latine et Anglice legere poteris. Quoad possumus, tantum Latine colloqui tentamus sed, cum inter sodales nostros gradus Latinitatis magnopere variet, plerumque in maiore parte conventus lingua Anglica utimur. Si plura scire vis, Iohannem Velptonium (vide supra) interrogare potes..

The next meeting will be held in the Basmati at 7.30 on Friday 26/1/24 in order to read from the middle of chapter 32 (Et cum interdixisset ..) to the end of chapter 35 of Suetonius' Life of Nero A description of the works of Suetonius as well as text with an interlinear English translation, notes and illustrations added (suetonius_nero_26-47_.doc ) can be downloaded from https://linguae.weebly.com/suetonius.html. If you want to attend, please inform John Whelpton by the 24th by email or on 93696180.

You can read below in both Latin and English about what happens in Latin Circles and about our rules. As far as possible, we try to talk only in Latin, but since the level of proficiency varies greatly among members, we normally use English for most of the meeting. For more information, contact John Whelpton (see above).

Ad epitomem rerum gestarum (Anglice scriptam) comparandam haec documenta deponite. Relatio de conventu proxime praeterito in Interreti inspici potest.

Download these files for a summary (in English) of previous discussions. Reports on the meetings since September 2016 are also available as separate pages on this site:

De rebus in Circulis Latinis agendis et regulis nostris infra et Latine et Anglice legere poteris. Quoad possumus, tantum Latine colloqui tentamus sed, cum inter sodales nostros gradus Latinitatis magnopere variet, plerumque in maiore parte conventus lingua Anglica utimur. Si plura scire vis, Iohannem Velptonium (vide supra) interrogare potes..

The next meeting will be held in the Basmati at 7.30 on Friday 26/1/24 in order to read from the middle of chapter 32 (Et cum interdixisset ..) to the end of chapter 35 of Suetonius' Life of Nero A description of the works of Suetonius as well as text with an interlinear English translation, notes and illustrations added (suetonius_nero_26-47_.doc ) can be downloaded from https://linguae.weebly.com/suetonius.html. If you want to attend, please inform John Whelpton by the 24th by email or on 93696180.

You can read below in both Latin and English about what happens in Latin Circles and about our rules. As far as possible, we try to talk only in Latin, but since the level of proficiency varies greatly among members, we normally use English for most of the meeting. For more information, contact John Whelpton (see above).

Ad epitomem rerum gestarum (Anglice scriptam) comparandam haec documenta deponite. Relatio de conventu proxime praeterito in Interreti inspici potest.

Download these files for a summary (in English) of previous discussions. Reports on the meetings since September 2016 are also available as separate pages on this site:

|

December 2010 - 14-9-12

|

12/10/12 - 21/3/14

|

|

| ||||||||||||

11/4/14 - 15/7/15 26/8/15 - 29/4/16

20/5/16 - 3/2/17

24/1/18 - 16/11/18

28/6/19 -

30/12/20 - 28/7/21

12/11/21 - 3/12/21

29/4/22 - 29/7/22

16/12/22 - 24/3/23

|

24/2/17 -29/12/17

6/12/18 -31/5/19

21/2/20 - 20/11/20

27/8/21 - 22/10/21

4/2/22 - 18/3/22

30/9/22 - 25/11/22

21/4/23 - 22/8/23

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Documenta infra posita sunt textus integer libri c.t. Ciceronis Filius, a Henrico Paoli compositus, et capitula in conventibus nostris prioribus recitata, quibus macra necnon commentarii additi sunt.

The documents below are the complete text of Henrico Paoli's Ciceronis Filius and the chapters of it which have been read in our previous meeings and to which macrons and notes have been added.

The documents below are the complete text of Henrico Paoli's Ciceronis Filius and the chapters of it which have been read in our previous meeings and to which macrons and notes have been added.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Relatio quoque de interrogatione Iohannis Elenorae Rykener infra posita est , quam mensibus Septembri et Octobri anno MMXXIII recitavimus.

Also placed below is the teport on the interrogation of John/Eleanor Rykener, which we read on september/October 2023.

Also placed below is the teport on the interrogation of John/Eleanor Rykener, which we read on september/October 2023.

| john-eleanor-rykener.doc | |

| File Size: | 1207 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

Documenta insequentia sunt elenchi verborum iuncturarumque quae in conventibus nostris usui sint. Primum est glossarium generale, cui adhuc multa addenda et corrigenda sunt, secundum versiones Anglicas nominum ferculorum Indicorum, tertium versiones Latinas praebet. Quartum est glossarium ad omnia genera ciborum necnon artem coquendi cenandique pertinentia, in quo vocabula quae in in Latina Classica non apparent litteris viridibus distinguuntur. Omnia documenta praeter primum ab Eugenio Yu parata sunt.

The folowing documents are lists of words and phrases meant to be of use in our meetings. the first is a general glossary which stil needs many additions and corrections. the second provides English versions of the names of Indian dishes and the third Latin ones. The fourth is a glossary covering all kinds of food and the art of cooking and dining and the fifth a list of terms connected with houses, flats and furniture. Al the documents except the first and the sixth were prepared by Eugene Yu.

The folowing documents are lists of words and phrases meant to be of use in our meetings. the first is a general glossary which stil needs many additions and corrections. the second provides English versions of the names of Indian dishes and the third Latin ones. The fourth is a glossary covering all kinds of food and the art of cooking and dining and the fifth a list of terms connected with houses, flats and furniture. Al the documents except the first and the sixth were prepared by Eugene Yu.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

`Basmati' caupona in via Conotensi prope portam `C' littera designatam stationis Metropolitanae Sheung Wan sita est. In hac charta geographica caupona littera `A' designata est.

The `Basmati' restaurant (`A' on the map) is on Connaught Road near Exit C from the Sheung Wan MTR station

The `Basmati' restaurant (`A' on the map) is on Connaught Road near Exit C from the Sheung Wan MTR station

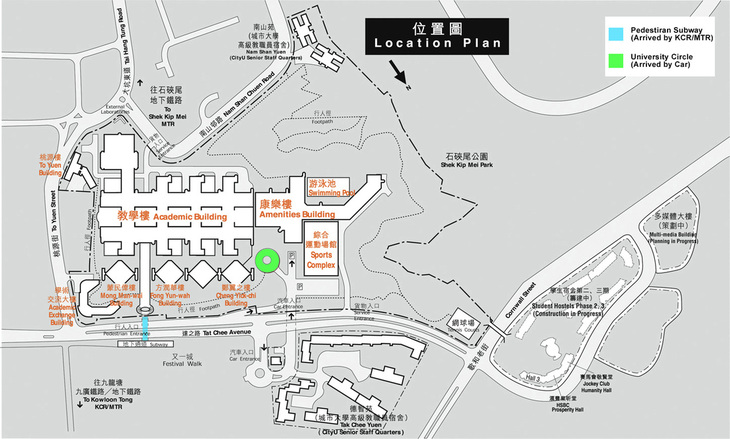

The City Chinese Resturant is on the 8th floor of the Amenities Block on the City University campus, which can be reached via the subway from Festival Walk. More detailed instructions are available here. It is also possible to reach the lift by going straight ahead from the subway into the Academic Building, taking the escalator on your right to the first floor and walking straight ahead.

Epistula Invitationis (2010)

Iohannes Velptonius omnibus Latinistis Honcongi habitantibus

Per tres quattuor annos in animo habebam societatem condere. in qua omnes Honcongenses quibus Latinitas viva cordi esset linguae usum exercere possent. Cum munus magistri linguae Anglicae in schola media nuper deposuerim, mihi otium nunc sufficit ut consilium exsequi tentem itaque hodie mihi propositum est vos omnes invitare ut sodales novae societatis – Circuli Latini Honcongensis – fiatis.

Credo vos omnes scire quid sit `Circulus Latinus’ sed, ut res satis clarae sint, haec verba de Circulo Londiniensi scripta reduplicavi :.

Circulus Latinus Londiniensis unus est e plurimis Circulis Latinis totius orbis terrarum qui statutis temporibus homines omne genus congregant qui Latine loqui student...Sicut plurimi alii Circuli Latini, malumus convenire in locum qui foveat convivalem aditum ad humanitatem cuius omnes possint participare, nempe in domum publicam --sic enim appellant Angli tabernas-- primo, si licet, cuiusque mensis Iovis die. Magna iucunditate omnibus de rebus Latine loqui solemus quas animum nostrum alliciunt, dum cervesiæ sextarios --ut fit apud Britannos-- bibimus vel cenamus. Sæpe etiam cum prope assidentibus sermones conserimus qui mirantur quanam lingua tam alacriter loquamur.

Spero nos quoque unoquoque mense vel (si satis otii non habebimus) binis mensibus semel conventuros esse ut Latine colloquamur. Mihi videtur Tabernam Ferroviariam (Railway Tavern), quae prope stationem ferroviariam in Magnosaepto (Tai Wai) sita est, aptam esse conventibus nostris habendis. Chartam geographicam adiunxi, in qua clariter demonstratur qua via illuc perveniatur.

Nihil refert si sodales Latine loquentes errores faciunt, sed maximi momenti est, dum conventus habeatur, omnes inter nos tantum Latine loqui. Non fieri potest quin in sermonibus nostris singula verba Anglica (vel Sinica vel Germanica!) interdum inseramus sed structura totius sententiae Latina remanere debet. Verbi gratia, si locutor vocabulum Latinum necessarium nescit, quaerere poterit `Quomodo `skier’ Latine dicitur?’ etc. Ut in aliis terris, eis qui Latine ipsi loqui nondum parati sunt, licebit aliorum sermones silenter audire

Me certiorem, quaeso, facite utrum participes esse velitis atque, si res vos tenet, quo/quibus diebus septimanae convenire vobis commodissimum futurum sit. Si in taberna magnam turbam et clamorem evitare volemus, vesperi maturius (sexta hora?) conveniendum erit, sed fortasse multis ante septimam horam ad tabernam pervenire difficile erit. De his rebus quoque sententias vestras colligere volo.

Si verba Latina mea obscura sunt, versionem anglicam infra positam videte. Respondete, quaeso, Latine vel Anglice, ut vobis ipsis placebit. Epistulam electronicam hic mittere potestis.

Optime valeatis

Dear All

For three or four years I’d been thinking of setting up an organisation in which all Hong Kong enthusiasts for `living Latin’ could practise using the language. As I’ve recently retired from my job as a secondary school English teacher I have enough spare time to try to carry out this plan. My purpose today is to invite you to become members of a new society – the Circulus Latinus Honcongensis.

I think you all know what a `Circulus Latinus’ is, but, to make everything sufficiently clear, here’s something written about the Circulus Latinus Londiniensis

The Circulus Latinus Londiniensis is one of a large number of Circuli Latini throughout the world which bring together on a regular basis people of all sorts who are keen to talk in Latin. Like most other Circuli Latini, we prefer to meet in a place that fosters a convivial and civilised atmosphere which all can share – viz. a `public house’ (the English term for a bar), if possible, on the first Thursday of every month. We talk very happily in Latin about every subject which takes our fancy while drinking pints of beer (as is the British custom) or having a meal. Often we also get into conversation with those sitting near us who wonder what language we’re talking in so energetically.

I hopw we will also be able to meet once a month or (if we’re short of time) once in two months to speak Latin. It seems to me that the Railway Tavern near the KCR station in Tai Wai would be suitable for holding our meetings. I’ve attached a map showing how to get there.

It doesn’t matter if members make mistakes when speaking Latin, but it’s very important that, while the meeting’s going on, we only use Latin among ourselves. It’s inevitable that we’ll sometimes slip individual English (or Chinese or German!)) words into the conversation but the overall sentence structure should remain Latin. For example, if a speaker doesn’t know the word needed in Latin, he can ask `Quomodo `skier’ Latine dicitur?’etc. As in other countries, those who are not yet ready to speak in Latin themselves will be allowed to listen quietly to others talking.

Please let me know whether you are willing to take part and, if you are interested, what day or days of the week would be most convenient for you to hold the meetings. If we want to avoid crowds and noise in the pub, we should meet earlier in the evening (6 p.m.?) but perhaps for many people it will be difficult to arrive before 7.

I look forward to hearing from you in Latin or English, as you prefer. You can send an email here.

Best wishes,

John

Epistula Invitationis (2010)

Iohannes Velptonius omnibus Latinistis Honcongi habitantibus

Per tres quattuor annos in animo habebam societatem condere. in qua omnes Honcongenses quibus Latinitas viva cordi esset linguae usum exercere possent. Cum munus magistri linguae Anglicae in schola media nuper deposuerim, mihi otium nunc sufficit ut consilium exsequi tentem itaque hodie mihi propositum est vos omnes invitare ut sodales novae societatis – Circuli Latini Honcongensis – fiatis.

Credo vos omnes scire quid sit `Circulus Latinus’ sed, ut res satis clarae sint, haec verba de Circulo Londiniensi scripta reduplicavi :.

Circulus Latinus Londiniensis unus est e plurimis Circulis Latinis totius orbis terrarum qui statutis temporibus homines omne genus congregant qui Latine loqui student...Sicut plurimi alii Circuli Latini, malumus convenire in locum qui foveat convivalem aditum ad humanitatem cuius omnes possint participare, nempe in domum publicam --sic enim appellant Angli tabernas-- primo, si licet, cuiusque mensis Iovis die. Magna iucunditate omnibus de rebus Latine loqui solemus quas animum nostrum alliciunt, dum cervesiæ sextarios --ut fit apud Britannos-- bibimus vel cenamus. Sæpe etiam cum prope assidentibus sermones conserimus qui mirantur quanam lingua tam alacriter loquamur.

Spero nos quoque unoquoque mense vel (si satis otii non habebimus) binis mensibus semel conventuros esse ut Latine colloquamur. Mihi videtur Tabernam Ferroviariam (Railway Tavern), quae prope stationem ferroviariam in Magnosaepto (Tai Wai) sita est, aptam esse conventibus nostris habendis. Chartam geographicam adiunxi, in qua clariter demonstratur qua via illuc perveniatur.

Nihil refert si sodales Latine loquentes errores faciunt, sed maximi momenti est, dum conventus habeatur, omnes inter nos tantum Latine loqui. Non fieri potest quin in sermonibus nostris singula verba Anglica (vel Sinica vel Germanica!) interdum inseramus sed structura totius sententiae Latina remanere debet. Verbi gratia, si locutor vocabulum Latinum necessarium nescit, quaerere poterit `Quomodo `skier’ Latine dicitur?’ etc. Ut in aliis terris, eis qui Latine ipsi loqui nondum parati sunt, licebit aliorum sermones silenter audire

Me certiorem, quaeso, facite utrum participes esse velitis atque, si res vos tenet, quo/quibus diebus septimanae convenire vobis commodissimum futurum sit. Si in taberna magnam turbam et clamorem evitare volemus, vesperi maturius (sexta hora?) conveniendum erit, sed fortasse multis ante septimam horam ad tabernam pervenire difficile erit. De his rebus quoque sententias vestras colligere volo.

Si verba Latina mea obscura sunt, versionem anglicam infra positam videte. Respondete, quaeso, Latine vel Anglice, ut vobis ipsis placebit. Epistulam electronicam hic mittere potestis.

Optime valeatis

Dear All

For three or four years I’d been thinking of setting up an organisation in which all Hong Kong enthusiasts for `living Latin’ could practise using the language. As I’ve recently retired from my job as a secondary school English teacher I have enough spare time to try to carry out this plan. My purpose today is to invite you to become members of a new society – the Circulus Latinus Honcongensis.

I think you all know what a `Circulus Latinus’ is, but, to make everything sufficiently clear, here’s something written about the Circulus Latinus Londiniensis

The Circulus Latinus Londiniensis is one of a large number of Circuli Latini throughout the world which bring together on a regular basis people of all sorts who are keen to talk in Latin. Like most other Circuli Latini, we prefer to meet in a place that fosters a convivial and civilised atmosphere which all can share – viz. a `public house’ (the English term for a bar), if possible, on the first Thursday of every month. We talk very happily in Latin about every subject which takes our fancy while drinking pints of beer (as is the British custom) or having a meal. Often we also get into conversation with those sitting near us who wonder what language we’re talking in so energetically.

I hopw we will also be able to meet once a month or (if we’re short of time) once in two months to speak Latin. It seems to me that the Railway Tavern near the KCR station in Tai Wai would be suitable for holding our meetings. I’ve attached a map showing how to get there.

It doesn’t matter if members make mistakes when speaking Latin, but it’s very important that, while the meeting’s going on, we only use Latin among ourselves. It’s inevitable that we’ll sometimes slip individual English (or Chinese or German!)) words into the conversation but the overall sentence structure should remain Latin. For example, if a speaker doesn’t know the word needed in Latin, he can ask `Quomodo `skier’ Latine dicitur?’etc. As in other countries, those who are not yet ready to speak in Latin themselves will be allowed to listen quietly to others talking.

Please let me know whether you are willing to take part and, if you are interested, what day or days of the week would be most convenient for you to hold the meetings. If we want to avoid crowds and noise in the pub, we should meet earlier in the evening (6 p.m.?) but perhaps for many people it will be difficult to arrive before 7.

I look forward to hearing from you in Latin or English, as you prefer. You can send an email here.

Best wishes,

John

SUBSIDIA AD SERMONES LATINOS

Sunt libri et situs interretiales qui subsidia ad linguae Latinae usum viva voce exercendum praebent. Paginae quas ad usum in Universitate Sinensi anno praeterito praeparavi de http://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/~lha/latin_intensive/download/WHELPTON_NOTES2.pdf deponi possunt, et alia colloquia a duobus magistris Americanis scripta (Colloquia Cottidiana). Si de vocalibus longis recte enuntiandis curatis, meminisse debetis errores esse in `Colloquiis Cottidianis’ . Nihilominus, dialogi ipsi nobis certissime usui sunt. Utilis etiam est liber c.t. Nos in Schola Latine Loquimur a magistro Belgico Thoma Elsaesser in initio saeculi praeterito scriptus, cuius editio anni 1909 in fine huius paginae invenietur. In hoc, tamen, longtitudo vocalium non indicatur et iuncturae magni momenti non Anglice sed francogallice reddundur. Neque quantitates indicantur in libro c.t. Colloquia Latino Sermone Conscripta, quem magistri Itali Balboni et Neri versione Italica et laudibus `Fidei Lictoriae' (sc. Fascismi) instructam anno 1937 ediderunt.`Gregorius Clavus' nunc iuncturas ad colloquendum apta ex scriptoibus classicis extraca in bloggo suo c.t. Conversational Latin componit. Sunt etiam indices iuncturarum et vocabulorum utilium a Carolo Meissner et Valterio Ripman compositae et nuper in Interreti a Carolo Rhaetico apud http://hiberna-cr.wikidot.com/downloads positae. In historia paedagogiae Latinae praeclarissimi sunt dialogi a Marturino Corderio in saeculo secimo sexto scipti et ab Arcadio Avellano in saeculo vigesimo emendati. Textum in situ Univesitatis Sancti Ludovici invenetis Postremo, non omittendus est liber in saeculo octavo decimo edito, c.t. `Familiares colloquendi formulae, in usum scholarum concinnatae' in quo inter alias sententias diversas invenitur `Dismissa schola, tibi dentes excutiam!'

Inter libros typis expressos, praeclarissimus est opus Iohannis Traupman, c.t. Conversational Latin for Oral Proficiency, quod apud bookdepository.com et (pretio maiore!) apud Amazon praebetur. Pars magna eius operis in interreti apud Google Books legi potest. Si vis, etiam poteris exemplum meum inspicere – qui primus rogabit, primus accipiet!. Exemplaria quoque habeo liberi Angelae Wilks c.t. Latin for Beginners et Sigridis Albert c.t. Cottidie Latine Collaquamur.

Acroasis Latina eodem titulo, a Sigride anno 2013 habita, apud TuTubulum praebetur: Pars I (25.06 incipit), Pars 2, Pars 3 Nulli sunt subtituli sed lente atque clare loquitur..

Potestis quoque per interrete apud situm Scholae (www.schola.ning) cum aliis Latinistis et scribendo et loquendo latine communicare. In situ meo (http://linguae.weebly.com/latin--greek.html) sunt etiam complures pelliculae (videos) in quibus dialogi Latini audiuntur.

Sunt etiam in Interreti pellicula quaedam longa (30 min), in qua professores de `Latinitate viva’ Anglice colloquuntur (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqOFnYgyRr8&NR=1), et pelliculae breviores in quo professores et discipuli apud Conventiculum Lexintoniense Latine colloquuntur (e.g. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0emFzJ0oCQ&NR=1)

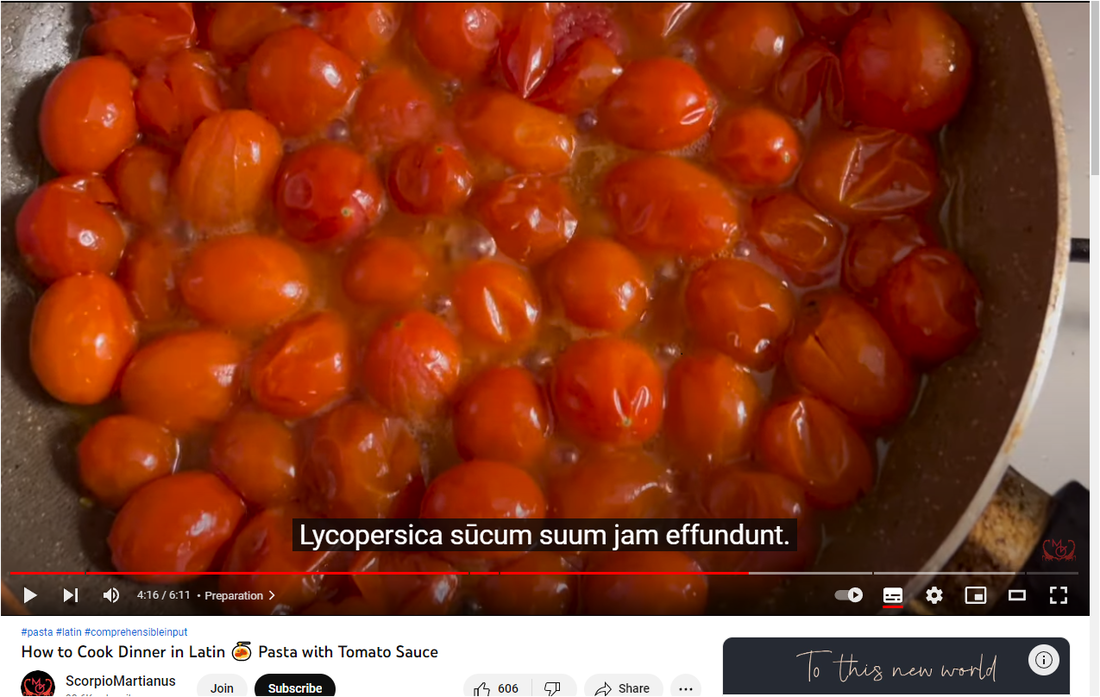

Maximi momenti sunt subsidia nova a magistris Americanis anno 2016 in Interreti posita:

Inceptum Latinum Audiendi (Latin Listening Project): series pellicularum in quibus magister vel magistra de re

quadem (e.g. Quae est fabula Graeca titi acceptissima, Ars coquendi etc.) 1-5 minutas loquitur

Quomododicitur.com: series dialogorum in quibus tres magistri de re singulari (e.g. De corpore sana, De nominibus) 15-20 minutis inter se colloquuntur. Colloquia in rete audiri re vel in computatrum in forma podcasti depromi possunt.

Utilissima quoque sunt subsidia quae apud www.latinitium.com praebentur, inter quae est vinculum ad congeriem septuaginta horas acroasium Latinarum in TuTubulo positarum.

AIDS FOR LATIN CONVERSATION

There are books and websites which provide help for using Latin in conversation. You can download Colloquia Latina, notes which I prepared last year for use in the Chinese University of Hong Kong and also Collloquia Cottidiana, dialogues prepared by two American teachers. If you are concerned about getting vowel length right, you need to remember that there are errors in their work, but it is still a very valuable resource. Also useful is the book Nos in Schola Latine Loquimur written by Belgian teacher Thomas Elsaesser, the 1909 edition of which can be downloaded from the bottom of this page. This, however, has no vowel length markings and key phrases are glossed in French, not English. Vowel quantitites are also missing in Colloquia Latino Sermone Conscripta, which two Italian teachers, Balboni and Neri, brought out in 1937, adding an Italian tranlation and aslo praise for `fides Lictoria' (sc. Fascism)! `Gregorius Clavus' is comiling a glossary of conversational phrases culled from various classical authors in his Conversational Latin blog. There are also the lists of useful phrases and words compiled by Charles Meissner et Walter Ripman recently placed on the Internet by Carolus Rhaeticus at http://hiberna-cr.wikidot.com/downloads. In the history of Latin teaching, the dialogues written by Maturinus Corderius in the16th century are very famous. Some of them can be found, as modified last century by Arcadius Avellanus, on the St. Louis University site. Mention should also be made of an 18th century book, Familiares colloquendi formulae, which includes amongst various other phrases `Dismissa schola, tibi dentes excutiam!' (`When school's over, I'll knock your teeth out!')

As for books, the best-known is John Traupman's Conversational Latin for Oral Proficiency, which is t available on bookdepository.com and(at a higher price!) from Amazon. A large part of the work can also be read online at Google Books. If you wish, you can also have a look at my copy - first come, first served! I also have copies of Angela Wilks' book, Latin for Beginners, and Sigrides Albert's Cottidie Latine Collaquamur. Sigrides 2013 Latin lecture with the same title can be viewed on YouTube: Part I (from 25.06), Part 2, Part 3 There are no subtitles but she speaks slowly and clearly.

You can also communicate with other Latinists in Latin (both written and spoken) on the Schola site, whilst my own site, Linguae also has several videos in which Latin can be heard. By registering with the Circulus Latinus Interretialis you can join a list of Latinists who converse with each other over the Skype internet phone system.

Also online are a 30-minute film in which professors speak in English about `Latin Immersion' and shorter films in which prefessors and students at the Lexington Conventiculum speak in Latin.

Two aids of very great importance were uploaded by American teachers in 2016:

Latin Listening Project: a series of videos in which a teacher talks for 1-5 minutes on a particular topic (e.g What is your favourite Greek story, the art of cooking etc.)

Quomododicitur.com: a series of dialogues in which three teachers talk together for 15-20 minutes on one individual

topic (e.g. On a healthy body, On names)

Also extremely useful are the resources available at www.latinitium.com , among which is a link to a playlist of 70 hours of Latin lectures uploaded to YouTube.

The Circulus Latinus Honcongensis is an experimental venture and, although to take a full part you will need to have a basic knowledge of Latin, there will be no fluent speakers present, and probably only two people who have attended Latin conversation sessions before, so we are bound to go slow and everyone will have a chance to follow. The rules also allow the use of individual English words provided the overall sentence structure remains in Latin. Detailed vocabulary help is available on the links above and in the vocabulary list below but useful phrases for getting started include:

Salvē! Hello! Iterum dīc, quaesō Say again, please.

Quid agis? How are you? Lentē, quaesō Slowly, please

Bene mē habeō I’m fine Anglicē In English

Quid est officium tuum? What’s your job? Hoc quid vocātur? What’s this called?

Nōn intellēxī I didn’t understand Cervisiam bibō I drink beer

Quōmodo dīcitur How do you say Vīnum rubrum, Red wine, please

_____Latīne? _____ in Latin? quaesō

Grātiās [tibi agō] Thanks Esne advocātus? Are you a lawyer?

Sum grammaticus I ’m a language teacher Prōsit! Cheers!

VOCĀBULA ET IUNCTŪRAE ŪTILĒS

(Stressed syllables shown in red but

words of two syllables, always stressed on the first, are often not marked )

Fundamentālia

Iterum dīc, quaesō Say again, please.

Lentē, quaesō Slowly, please

Maiōre vōcē, quaesō Louder, please

Scrībe, quaesō Write it down, please

Nōn intellegō I don’t understand

Intellegisne/Intellegitisne? Do you understand?

Nōn intellēxī I didn’t understand?

Intellēxistīne/Intellēxistisne? Did you understand or Have you understood?

Quōmodo dīcitur_____Latīnē/Anglicē How do you say _______ in Latin/English

Hoc quid vocātur? What’s this called?

Ita (est), Etiam Yes

Minimē Not at all

Mihi ignosce Sorry

Salutātiōnēs /Introductiōnēs/Valēdictiōnēs etc,

Salvē/salvēte Hello

Quid/Quod est tibi nōmen? What’s your name

Mihi nōmen (Anglicum/Sīnicum/Latīnum) My (English/Chinese/Latin) name is _________

est_______

Quid agis? How are you

Bene mē habeō I’m fine

Mihi abeundum est or Discēdere dēbeō I’ve got to go

Valē/valēte Goodbye

Usque ad proximum mēnsem/proximam Till next month/week

septimānam

In taberna

Sextārium cervisiae requīrō, quaesō I want a pint of beer, please

Vīnum rubrum/album requīrit He/She wants red/white wine.

Lāminās [solanōrum] requīris? Do you want some [potato] crisps(Americānē chips)?

Ministrōs rōgā ut lāminās in corbem dēpōnant Ask the staff to put the crisps in a basket

Aliquidne requīris? Do you want anything?

Velisne ut tibi potiōnem afferam? Would you like me to get you a drink?

Pōculum magnum an parvum requīris? Do you want a large glass or a small one?

Habentne pōma fricta? Do they have chips (Americānē french fries)?

Minister/ministra ad mensam veniet sed facilius The waiter/waitress will come to the table but it’s easier to

est ad cartibulum īre go to the bar

Quantī cōnstat/cōnstant? How much does it/do they cost ?

Ubi est lātrīna? Where’s the toilet

Ibi /in angulō sinistrō/dexterō est It’s there/in the left-hand/right-hand corner

Spicula iaciunt They’re throwing darts

Ubi est tabella spiculāria? Where’s the dart board?

Vīsne prope fenestram/iānuam sedēre? Do you want to sit near the window/door

Nōn est necessārium surgere There’s no need to get up

Quot sellae sunt? How many seats are there?

Hōra et diēs

Quota est hōra/Quot hōrae sunt? What time is it ?

Est prīma/secunda/tertia/quarta/quīnta/sexta/ It’s 1..12 [.15/30/45]

septima/octāva/nōna/decima/undecima/ [in the day/at night]

duodecima [diēī/noctis]hōra et quadrāns/

dimidia/dōdrāns/

Petrus quotā hōrā perveniet? What time will Peter arrive?

Septimā hōrā et quadrante/dimidiā/dōdrante At 7.15/7.30/7/45

Dē tē ipsō (recitātiō) (pelliculae animātae)

Quot annōs nātus/nāta es? How old are you?

------ annōs nātus/nāta sum I’m ____ years old

Habēsne fīliōs vel fīliās? Do you have any sons or daughters?

Habeō nūllum/ūnum fīlium sed/et nūllam/ I have no/one son and/but no/one daughter

ūnam fīliam

Habeō duōs fīliōs/duās fīliās I have two sons/daughters

Unde venīs? Where do you come from ?

Britannus/a sum I’m British American Korean French German Chinese

Canādiānus /a Americānus/a Coreānus/a A ustralian

Francogāllus/a Germānus/a Sīnēnsis

Austrāliānus

Ubi nātus/a es? Where were you born ?

Ubi habitās? Where do you live

Antequam Honcongum vēnistī, ubi habitābās? Before you came to HK, where did you live?

Nottinghāmiae/Londīnī/ Honcongī/Berolīnī/ I was born/live/lived in Nottingham/London/Hong Kong/

in īnsulā Honcongō/Novemdracōnibus/ Paris/Hong Kong Island/ Kowloon/

Lutetiae/ nātus(nāta) sum/habitō/ habitābam

Quem quaestum facis?/Quid est officium tuum? How do you make a living? What is your job? What post

Quō mūnere fungeris are you in

Esne advocātus/a? Are you a lawyer?

Fīlius tuus/fīlia tua maior quem quaestum facit? What’s your elder son’s/daughter’s job?

Sum argentārius/a - grammaticus/a - I’m a banker/language teacher/professor/doctor/journalist

professor/profestrix - medicus/a - researcher/policeman/lawyer/teacher/priest/historian/

investigātor/investigātrix - custōs pūblicus/a - writer/businessman/civil servant/editor/government

diurnārius/a - advocātus/a - magister/magistra contractor/housewife/theatre administrator/student

sacerdōs - historicus/a scrīptor/scrīptrix -

mercātor/mercātrix - officiālis - redāctor -

mercātor/mercātrix officiālis - māterfamiliās -

administrātor theātrālis - discipulus/discipula

Dē linguīs (recitātiō)

Cūr linguam Latīnam didicistī? Why did you learn Latin?

Nōn didicī I didn’t learn it!

Quia cultūra atque historia antīquae mē Because ancient culture and history attract me

alliciunt

Quia mē linguae tenent/alliciunt. Because languages interest/attract me

Quia in scholā meā coācti sumus Because we were forced to learn Latin in school

linguam Latīnam discere .

Quibus aliīs linguīs loqueris? What other languages do you speak?

Francogallicē, Germānicē, Sīnicē (sermōne French German Chinese (Cantonese or Putonghua)

Cantonēnsī vel sermōne normālī), Iaponicē, Japanese Korean Polish Spanish Greek

Coreānicē, Polonicē, Hispānicē, Graecē

Cur Latīne loquī vīs? Why do you want to speak Latin?

Quia quī loqui nōn scit, linguā rēvērā Because if you can’t speak a language you haven’t really

nōn callet. mastered it

Quia Latīnē loquī iūcundum est Because it’s fun to speak Latin

Quia novae experientiae mē dēlectant Because I like new experiences

Quot annōs linguam Latīnam discis/didicistī? How many years have you been learning/ did you learn Latin

Prōnuntiātū classicō an ecclēsiasticō ūteris? Do you use the classical or the church pronunciation?

Quae sunt discrīmina prīncipālia? What are the main differences?

Modō ecclēsiasticō vel mediaevālī, `c’ et `g’ In the ecclesiastical or medieval style, the consonants `c’ and

cōnsonantēs, cum ante `i’ vel `e’ vōcālēs `g’, when occurring before the vowels `i’ or `e’, are not hard

occurrant, nōn dūrae sed mollēs sunt – ut but soft – the way the letters `ch’ and `j’ are pronounced in

`ch’ et `j’ litterae Anglicē dīcuntur. Modō English. In the classical style, these consonants are always

classicō hae cōnsonantēs semper ut in `cat’ pronounced as in the English words `cat’ or `game’.

vel `game’ vocābulīs Anglicīs ēnūntiantur.

Prōnūntiātus `ae’ diphthongī temporibus In Cicero’s time, the pronunciation of the diphthong `ae’ was

Cicerōnis erat similis vōcālī in `die’ vocābulō similar to that of the vowel in the English word `die’, but

Anglicō, sed aevō mediaevālī ut `ay’ in `day’. in the medieval period it was pronounced like `ay’ in

ēnuntiābātur, English `day’.

Aevō classicō `v’ littera ut Anglica `w’, In the classical period the letter `v’ sounded like the

dīcēbātur sed aevō mediaevālī similis erat English `w’, but in medieval times it was like the English `v’

Anglicae `v’ .

Vīta Honcongēnsis (recitātiō)

Quae sunt beneficia vītae Honcongēnsis? What are the advantages of living in Hong Kong?

Quaestum invenīre professiōnālibus facile est It’s easy for professionals to find a job.

Pecūniae comparandae ānsae multae sunt There are lots of opportunities to make money.

Omnia oblectāmenta urbāna praebentur sed All the amusements of the city are available but we can

facile in rūs pulchrum pervenīmus. easily get into beautiful countryside

Aestāte in ōrīs iūcundis sedēre et in marī natāre In the summer we can sit on nice beaches and swim in the

possumus sea

Per tōtum annum inter montēs errāre We can hike in the hills all year round.

possumus

Hīc cultūra orientālis adest, occidentālis. It combines eastern and western culture.

quoque

Facillimē ad aliās terrās itinera facere We can travel to other countries very easily.

possumus

A fūribus vel latrōnibus rārissime vexāmur, We aren’t often bothered by thieves or robbers and we’re

in viīs sine timōre ambulāmus. not afraid when we walk in the streets.

Commeātus pūblicus optimus est. Public transport is first-rate.

Sententiās nostrās līberē exprimere possumus. We’re free to express our opinions.

Magna pars incolārum Anglicē commūnicāre Most local people can communicate in English

possunt.

Quae sunt detrimenta vītae nostrae? What are the disadvantages of our lives here?

Quī ingeniīs vel artibus nōn dōnātī sunt, Those who lack talents or skills suffer from poverty.

paupertāte īnflīguntur.

Dīvitēs dīvitiōrēs, pauperēs pauperiōrēs fīunt The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

Āēr, aqua, terra inquinātae sunt. Air, water and land are polluted

In minimīs diaetīs habitāmus. We live in very small flats.

In urbe ubīque sunt turbae strepitusque. In the city there are crowds and noise everywhere.

Plērīque Honcongēnses in officīnīs multās Most Hongkongers have to stay long hours in their

hōrās remanēre dēbent. workplaces.

Discipulī vesperī multās per hōrās pēnsa Students need to spend many hours doing homework in

dēbent facere the evening.

In scholīs lycaeīsque verba ēdiscere maiōris In schools rote learning is often more important than real

mōmentī saepe est quam rem intellegere understanding.

Conductōrēs operis saepe crūdēlēs sunt Employers are often harsh.

Populus iūs nōn habet ēligendī omnēs The people do not have the right to choose all their rulers.

rēctōrēs suōs

Difficile est sermōnem Cantonēnsem discere. It’s difficult to learn Cantonese.

Honcongī quae regiō tē maxime dēlectat? What area of Hong kong do you like best?

Tsim Sha Tsui et Centrālem amō quod I love Tsim Sha Tsui and Central because I like big hotels

magna dēversōria tabernaeque et activitātēs and shops and cultural activities . I like the New Territories

cultūrālēs mihi placent. Terrās Novās et and the Outlying Islands because we have peace and quiet

Īnsulās Remōtiōrēs amō quod pācem et there

silentium ibi habēmus

Vīta cottidiāna recitātiō [n.b. the curent recordng still has `lactem', an error for the correct accusative form `lac']

Quotā hōrā māne surgis? What time do you get up in the morning?

Sextā hōrā et dimidiā 6.30

Septimā hōrā et quadrante 7.15

Balneō māne an vesperī ūteris? Do you have a bath in the morning or the evening?

Plērumque māne. In soliō nōn sedeō, balneō Generally in the morning. I don't sit in the bathtub but have a

plūviō ūtor. shower.

Quotā hōrā ientāculum sūmis? What time do you have breakfast?

Octāvā hōrā At eight o’clock.

Quid edis? What do you eat?

Pānem tostum /frūctūs/ ova frīcta et Toast/fruit/fried eggs and bacon/cereals

lardum/cereālia

Quid bibis? What do you have to drink?

Theam/caffeam/lac/aurantiī succum Tea/coffee/milk/orange juice

Quotā hōrā ad officīnam proficisceris? What time do you leave for work?

Octāvā hōrā et dōdrante At 8.45

Domī labōrō. I work at home

Nōn est hōra cōnstitūta There's no fixed time.

Quantō temporis ad officīnam pervenīs? How long does it take you to get to work?

Quinquaginta minūtīs Fifty minutes.

Iter quamdiu terit? How long does the journey take?

Dimidiam hōram Half an hour

Quōmodo iter facis? How do you travel?

Autoraedā/Raedā longā/Tramine/Currū I go by car/bus/train/tram and then walk

ēlectricō vehor deinde ambulō.

Birotā ūtor. I use a bike

Ubi prandium sūmis? Where do you have lunch

In caupōnā prope officīnam/universitātem In a restaurant near my work/university

Quid edis? What do you eat?

Pastillum fartum/Collӯram/Iūs collӯricum/ A sandwich/noodles/soup noodles/rice/dim sum

Orӯzam/Cuppēdiolās

Quotā horā ab officīnā proficisceris? What time do you leave work?

Sextā hōrā et dimidiā At 6.30

Vesperī quid facis? What do you do in the evening?

Cēnam coquō (ancillam nōn habeō) deinde I cook dinner (I don’t have a maid), then watch TV or read a

tēlevīsiōnem spectō vel librum legō. a book. Sometimes I dust the furniture or do other

interdum suppelectilem detergeō vel housework. I also have to make the bed because there’s not

aliās operās domesticās facio. Lectum time for that in the morning.

quoque sternere dēbeō quod māne tempus

nōn sufficit

Quid edis vesperī? What do you eat in the evening?

Varium est. Saepe būbulam vel porcīnam It varies. I often have roast beef or pork with fried potatoes

assam ūnā cum solānīs frīctīs et holeribus and vegetables. Usually I drink beer or wine.

edō. Plērumque cervisiam vel vīnum bibō.

Domī furculā cultellōque an bacillīs ūteris? Do you use a knife and fork or chopsticks at home?

Sī orӯzam vel collӯram edō, bacillīs, If I’m having rice or noodles I use chopsticks, if it’s

sī cibum occidentālem, cultellō et furculā. Western food, a knife and fork.

Quandō cubitum īs? When do you go to bed?

Inter hōrās ūndecimam et duodecimam. Between 11 and 12. I normally listen to the radio before I

Soleō antequam dormiam, radiophōnum go to sleep

audīre,

Sunt libri et situs interretiales qui subsidia ad linguae Latinae usum viva voce exercendum praebent. Paginae quas ad usum in Universitate Sinensi anno praeterito praeparavi de http://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/~lha/latin_intensive/download/WHELPTON_NOTES2.pdf deponi possunt, et alia colloquia a duobus magistris Americanis scripta (Colloquia Cottidiana). Si de vocalibus longis recte enuntiandis curatis, meminisse debetis errores esse in `Colloquiis Cottidianis’ . Nihilominus, dialogi ipsi nobis certissime usui sunt. Utilis etiam est liber c.t. Nos in Schola Latine Loquimur a magistro Belgico Thoma Elsaesser in initio saeculi praeterito scriptus, cuius editio anni 1909 in fine huius paginae invenietur. In hoc, tamen, longtitudo vocalium non indicatur et iuncturae magni momenti non Anglice sed francogallice reddundur. Neque quantitates indicantur in libro c.t. Colloquia Latino Sermone Conscripta, quem magistri Itali Balboni et Neri versione Italica et laudibus `Fidei Lictoriae' (sc. Fascismi) instructam anno 1937 ediderunt.`Gregorius Clavus' nunc iuncturas ad colloquendum apta ex scriptoibus classicis extraca in bloggo suo c.t. Conversational Latin componit. Sunt etiam indices iuncturarum et vocabulorum utilium a Carolo Meissner et Valterio Ripman compositae et nuper in Interreti a Carolo Rhaetico apud http://hiberna-cr.wikidot.com/downloads positae. In historia paedagogiae Latinae praeclarissimi sunt dialogi a Marturino Corderio in saeculo secimo sexto scipti et ab Arcadio Avellano in saeculo vigesimo emendati. Textum in situ Univesitatis Sancti Ludovici invenetis Postremo, non omittendus est liber in saeculo octavo decimo edito, c.t. `Familiares colloquendi formulae, in usum scholarum concinnatae' in quo inter alias sententias diversas invenitur `Dismissa schola, tibi dentes excutiam!'

Inter libros typis expressos, praeclarissimus est opus Iohannis Traupman, c.t. Conversational Latin for Oral Proficiency, quod apud bookdepository.com et (pretio maiore!) apud Amazon praebetur. Pars magna eius operis in interreti apud Google Books legi potest. Si vis, etiam poteris exemplum meum inspicere – qui primus rogabit, primus accipiet!. Exemplaria quoque habeo liberi Angelae Wilks c.t. Latin for Beginners et Sigridis Albert c.t. Cottidie Latine Collaquamur.

Acroasis Latina eodem titulo, a Sigride anno 2013 habita, apud TuTubulum praebetur: Pars I (25.06 incipit), Pars 2, Pars 3 Nulli sunt subtituli sed lente atque clare loquitur..

Potestis quoque per interrete apud situm Scholae (www.schola.ning) cum aliis Latinistis et scribendo et loquendo latine communicare. In situ meo (http://linguae.weebly.com/latin--greek.html) sunt etiam complures pelliculae (videos) in quibus dialogi Latini audiuntur.

Sunt etiam in Interreti pellicula quaedam longa (30 min), in qua professores de `Latinitate viva’ Anglice colloquuntur (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqOFnYgyRr8&NR=1), et pelliculae breviores in quo professores et discipuli apud Conventiculum Lexintoniense Latine colloquuntur (e.g. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0emFzJ0oCQ&NR=1)

Maximi momenti sunt subsidia nova a magistris Americanis anno 2016 in Interreti posita:

Inceptum Latinum Audiendi (Latin Listening Project): series pellicularum in quibus magister vel magistra de re

quadem (e.g. Quae est fabula Graeca titi acceptissima, Ars coquendi etc.) 1-5 minutas loquitur

Quomododicitur.com: series dialogorum in quibus tres magistri de re singulari (e.g. De corpore sana, De nominibus) 15-20 minutis inter se colloquuntur. Colloquia in rete audiri re vel in computatrum in forma podcasti depromi possunt.

Utilissima quoque sunt subsidia quae apud www.latinitium.com praebentur, inter quae est vinculum ad congeriem septuaginta horas acroasium Latinarum in TuTubulo positarum.

AIDS FOR LATIN CONVERSATION

There are books and websites which provide help for using Latin in conversation. You can download Colloquia Latina, notes which I prepared last year for use in the Chinese University of Hong Kong and also Collloquia Cottidiana, dialogues prepared by two American teachers. If you are concerned about getting vowel length right, you need to remember that there are errors in their work, but it is still a very valuable resource. Also useful is the book Nos in Schola Latine Loquimur written by Belgian teacher Thomas Elsaesser, the 1909 edition of which can be downloaded from the bottom of this page. This, however, has no vowel length markings and key phrases are glossed in French, not English. Vowel quantitites are also missing in Colloquia Latino Sermone Conscripta, which two Italian teachers, Balboni and Neri, brought out in 1937, adding an Italian tranlation and aslo praise for `fides Lictoria' (sc. Fascism)! `Gregorius Clavus' is comiling a glossary of conversational phrases culled from various classical authors in his Conversational Latin blog. There are also the lists of useful phrases and words compiled by Charles Meissner et Walter Ripman recently placed on the Internet by Carolus Rhaeticus at http://hiberna-cr.wikidot.com/downloads. In the history of Latin teaching, the dialogues written by Maturinus Corderius in the16th century are very famous. Some of them can be found, as modified last century by Arcadius Avellanus, on the St. Louis University site. Mention should also be made of an 18th century book, Familiares colloquendi formulae, which includes amongst various other phrases `Dismissa schola, tibi dentes excutiam!' (`When school's over, I'll knock your teeth out!')

As for books, the best-known is John Traupman's Conversational Latin for Oral Proficiency, which is t available on bookdepository.com and(at a higher price!) from Amazon. A large part of the work can also be read online at Google Books. If you wish, you can also have a look at my copy - first come, first served! I also have copies of Angela Wilks' book, Latin for Beginners, and Sigrides Albert's Cottidie Latine Collaquamur. Sigrides 2013 Latin lecture with the same title can be viewed on YouTube: Part I (from 25.06), Part 2, Part 3 There are no subtitles but she speaks slowly and clearly.

You can also communicate with other Latinists in Latin (both written and spoken) on the Schola site, whilst my own site, Linguae also has several videos in which Latin can be heard. By registering with the Circulus Latinus Interretialis you can join a list of Latinists who converse with each other over the Skype internet phone system.

Also online are a 30-minute film in which professors speak in English about `Latin Immersion' and shorter films in which prefessors and students at the Lexington Conventiculum speak in Latin.

Two aids of very great importance were uploaded by American teachers in 2016:

Latin Listening Project: a series of videos in which a teacher talks for 1-5 minutes on a particular topic (e.g What is your favourite Greek story, the art of cooking etc.)

Quomododicitur.com: a series of dialogues in which three teachers talk together for 15-20 minutes on one individual

topic (e.g. On a healthy body, On names)

Also extremely useful are the resources available at www.latinitium.com , among which is a link to a playlist of 70 hours of Latin lectures uploaded to YouTube.

The Circulus Latinus Honcongensis is an experimental venture and, although to take a full part you will need to have a basic knowledge of Latin, there will be no fluent speakers present, and probably only two people who have attended Latin conversation sessions before, so we are bound to go slow and everyone will have a chance to follow. The rules also allow the use of individual English words provided the overall sentence structure remains in Latin. Detailed vocabulary help is available on the links above and in the vocabulary list below but useful phrases for getting started include:

Salvē! Hello! Iterum dīc, quaesō Say again, please.

Quid agis? How are you? Lentē, quaesō Slowly, please

Bene mē habeō I’m fine Anglicē In English

Quid est officium tuum? What’s your job? Hoc quid vocātur? What’s this called?

Nōn intellēxī I didn’t understand Cervisiam bibō I drink beer

Quōmodo dīcitur How do you say Vīnum rubrum, Red wine, please

_____Latīne? _____ in Latin? quaesō

Grātiās [tibi agō] Thanks Esne advocātus? Are you a lawyer?

Sum grammaticus I ’m a language teacher Prōsit! Cheers!

VOCĀBULA ET IUNCTŪRAE ŪTILĒS

(Stressed syllables shown in red but

words of two syllables, always stressed on the first, are often not marked )

Fundamentālia

Iterum dīc, quaesō Say again, please.

Lentē, quaesō Slowly, please

Maiōre vōcē, quaesō Louder, please

Scrībe, quaesō Write it down, please

Nōn intellegō I don’t understand

Intellegisne/Intellegitisne? Do you understand?

Nōn intellēxī I didn’t understand?

Intellēxistīne/Intellēxistisne? Did you understand or Have you understood?

Quōmodo dīcitur_____Latīnē/Anglicē How do you say _______ in Latin/English

Hoc quid vocātur? What’s this called?

Ita (est), Etiam Yes

Minimē Not at all

Mihi ignosce Sorry

Salutātiōnēs /Introductiōnēs/Valēdictiōnēs etc,

Salvē/salvēte Hello

Quid/Quod est tibi nōmen? What’s your name

Mihi nōmen (Anglicum/Sīnicum/Latīnum) My (English/Chinese/Latin) name is _________

est_______

Quid agis? How are you

Bene mē habeō I’m fine

Mihi abeundum est or Discēdere dēbeō I’ve got to go

Valē/valēte Goodbye

Usque ad proximum mēnsem/proximam Till next month/week

septimānam

In taberna

Sextārium cervisiae requīrō, quaesō I want a pint of beer, please

Vīnum rubrum/album requīrit He/She wants red/white wine.

Lāminās [solanōrum] requīris? Do you want some [potato] crisps(Americānē chips)?

Ministrōs rōgā ut lāminās in corbem dēpōnant Ask the staff to put the crisps in a basket

Aliquidne requīris? Do you want anything?

Velisne ut tibi potiōnem afferam? Would you like me to get you a drink?

Pōculum magnum an parvum requīris? Do you want a large glass or a small one?

Habentne pōma fricta? Do they have chips (Americānē french fries)?

Minister/ministra ad mensam veniet sed facilius The waiter/waitress will come to the table but it’s easier to

est ad cartibulum īre go to the bar

Quantī cōnstat/cōnstant? How much does it/do they cost ?

Ubi est lātrīna? Where’s the toilet

Ibi /in angulō sinistrō/dexterō est It’s there/in the left-hand/right-hand corner

Spicula iaciunt They’re throwing darts

Ubi est tabella spiculāria? Where’s the dart board?

Vīsne prope fenestram/iānuam sedēre? Do you want to sit near the window/door

Nōn est necessārium surgere There’s no need to get up

Quot sellae sunt? How many seats are there?

Hōra et diēs

Quota est hōra/Quot hōrae sunt? What time is it ?

Est prīma/secunda/tertia/quarta/quīnta/sexta/ It’s 1..12 [.15/30/45]

septima/octāva/nōna/decima/undecima/ [in the day/at night]

duodecima [diēī/noctis]hōra et quadrāns/

dimidia/dōdrāns/

Petrus quotā hōrā perveniet? What time will Peter arrive?

Septimā hōrā et quadrante/dimidiā/dōdrante At 7.15/7.30/7/45

Dē tē ipsō (recitātiō) (pelliculae animātae)

Quot annōs nātus/nāta es? How old are you?

------ annōs nātus/nāta sum I’m ____ years old

Habēsne fīliōs vel fīliās? Do you have any sons or daughters?

Habeō nūllum/ūnum fīlium sed/et nūllam/ I have no/one son and/but no/one daughter

ūnam fīliam

Habeō duōs fīliōs/duās fīliās I have two sons/daughters

Unde venīs? Where do you come from ?

Britannus/a sum I’m British American Korean French German Chinese

Canādiānus /a Americānus/a Coreānus/a A ustralian

Francogāllus/a Germānus/a Sīnēnsis

Austrāliānus

Ubi nātus/a es? Where were you born ?

Ubi habitās? Where do you live

Antequam Honcongum vēnistī, ubi habitābās? Before you came to HK, where did you live?

Nottinghāmiae/Londīnī/ Honcongī/Berolīnī/ I was born/live/lived in Nottingham/London/Hong Kong/

in īnsulā Honcongō/Novemdracōnibus/ Paris/Hong Kong Island/ Kowloon/

Lutetiae/ nātus(nāta) sum/habitō/ habitābam

Quem quaestum facis?/Quid est officium tuum? How do you make a living? What is your job? What post

Quō mūnere fungeris are you in

Esne advocātus/a? Are you a lawyer?

Fīlius tuus/fīlia tua maior quem quaestum facit? What’s your elder son’s/daughter’s job?

Sum argentārius/a - grammaticus/a - I’m a banker/language teacher/professor/doctor/journalist

professor/profestrix - medicus/a - researcher/policeman/lawyer/teacher/priest/historian/

investigātor/investigātrix - custōs pūblicus/a - writer/businessman/civil servant/editor/government

diurnārius/a - advocātus/a - magister/magistra contractor/housewife/theatre administrator/student

sacerdōs - historicus/a scrīptor/scrīptrix -

mercātor/mercātrix - officiālis - redāctor -

mercātor/mercātrix officiālis - māterfamiliās -

administrātor theātrālis - discipulus/discipula

Dē linguīs (recitātiō)

Cūr linguam Latīnam didicistī? Why did you learn Latin?

Nōn didicī I didn’t learn it!

Quia cultūra atque historia antīquae mē Because ancient culture and history attract me

alliciunt

Quia mē linguae tenent/alliciunt. Because languages interest/attract me

Quia in scholā meā coācti sumus Because we were forced to learn Latin in school

linguam Latīnam discere .

Quibus aliīs linguīs loqueris? What other languages do you speak?

Francogallicē, Germānicē, Sīnicē (sermōne French German Chinese (Cantonese or Putonghua)

Cantonēnsī vel sermōne normālī), Iaponicē, Japanese Korean Polish Spanish Greek

Coreānicē, Polonicē, Hispānicē, Graecē

Cur Latīne loquī vīs? Why do you want to speak Latin?

Quia quī loqui nōn scit, linguā rēvērā Because if you can’t speak a language you haven’t really

nōn callet. mastered it

Quia Latīnē loquī iūcundum est Because it’s fun to speak Latin

Quia novae experientiae mē dēlectant Because I like new experiences

Quot annōs linguam Latīnam discis/didicistī? How many years have you been learning/ did you learn Latin

Prōnuntiātū classicō an ecclēsiasticō ūteris? Do you use the classical or the church pronunciation?

Quae sunt discrīmina prīncipālia? What are the main differences?

Modō ecclēsiasticō vel mediaevālī, `c’ et `g’ In the ecclesiastical or medieval style, the consonants `c’ and

cōnsonantēs, cum ante `i’ vel `e’ vōcālēs `g’, when occurring before the vowels `i’ or `e’, are not hard

occurrant, nōn dūrae sed mollēs sunt – ut but soft – the way the letters `ch’ and `j’ are pronounced in

`ch’ et `j’ litterae Anglicē dīcuntur. Modō English. In the classical style, these consonants are always

classicō hae cōnsonantēs semper ut in `cat’ pronounced as in the English words `cat’ or `game’.

vel `game’ vocābulīs Anglicīs ēnūntiantur.

Prōnūntiātus `ae’ diphthongī temporibus In Cicero’s time, the pronunciation of the diphthong `ae’ was

Cicerōnis erat similis vōcālī in `die’ vocābulō similar to that of the vowel in the English word `die’, but

Anglicō, sed aevō mediaevālī ut `ay’ in `day’. in the medieval period it was pronounced like `ay’ in

ēnuntiābātur, English `day’.

Aevō classicō `v’ littera ut Anglica `w’, In the classical period the letter `v’ sounded like the

dīcēbātur sed aevō mediaevālī similis erat English `w’, but in medieval times it was like the English `v’

Anglicae `v’ .

Vīta Honcongēnsis (recitātiō)

Quae sunt beneficia vītae Honcongēnsis? What are the advantages of living in Hong Kong?

Quaestum invenīre professiōnālibus facile est It’s easy for professionals to find a job.

Pecūniae comparandae ānsae multae sunt There are lots of opportunities to make money.

Omnia oblectāmenta urbāna praebentur sed All the amusements of the city are available but we can

facile in rūs pulchrum pervenīmus. easily get into beautiful countryside

Aestāte in ōrīs iūcundis sedēre et in marī natāre In the summer we can sit on nice beaches and swim in the

possumus sea

Per tōtum annum inter montēs errāre We can hike in the hills all year round.

possumus

Hīc cultūra orientālis adest, occidentālis. It combines eastern and western culture.

quoque

Facillimē ad aliās terrās itinera facere We can travel to other countries very easily.

possumus

A fūribus vel latrōnibus rārissime vexāmur, We aren’t often bothered by thieves or robbers and we’re

in viīs sine timōre ambulāmus. not afraid when we walk in the streets.

Commeātus pūblicus optimus est. Public transport is first-rate.

Sententiās nostrās līberē exprimere possumus. We’re free to express our opinions.

Magna pars incolārum Anglicē commūnicāre Most local people can communicate in English

possunt.

Quae sunt detrimenta vītae nostrae? What are the disadvantages of our lives here?

Quī ingeniīs vel artibus nōn dōnātī sunt, Those who lack talents or skills suffer from poverty.

paupertāte īnflīguntur.

Dīvitēs dīvitiōrēs, pauperēs pauperiōrēs fīunt The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

Āēr, aqua, terra inquinātae sunt. Air, water and land are polluted

In minimīs diaetīs habitāmus. We live in very small flats.

In urbe ubīque sunt turbae strepitusque. In the city there are crowds and noise everywhere.

Plērīque Honcongēnses in officīnīs multās Most Hongkongers have to stay long hours in their

hōrās remanēre dēbent. workplaces.

Discipulī vesperī multās per hōrās pēnsa Students need to spend many hours doing homework in

dēbent facere the evening.

In scholīs lycaeīsque verba ēdiscere maiōris In schools rote learning is often more important than real

mōmentī saepe est quam rem intellegere understanding.

Conductōrēs operis saepe crūdēlēs sunt Employers are often harsh.

Populus iūs nōn habet ēligendī omnēs The people do not have the right to choose all their rulers.

rēctōrēs suōs

Difficile est sermōnem Cantonēnsem discere. It’s difficult to learn Cantonese.

Honcongī quae regiō tē maxime dēlectat? What area of Hong kong do you like best?

Tsim Sha Tsui et Centrālem amō quod I love Tsim Sha Tsui and Central because I like big hotels

magna dēversōria tabernaeque et activitātēs and shops and cultural activities . I like the New Territories

cultūrālēs mihi placent. Terrās Novās et and the Outlying Islands because we have peace and quiet

Īnsulās Remōtiōrēs amō quod pācem et there

silentium ibi habēmus

Vīta cottidiāna recitātiō [n.b. the curent recordng still has `lactem', an error for the correct accusative form `lac']

Quotā hōrā māne surgis? What time do you get up in the morning?

Sextā hōrā et dimidiā 6.30

Septimā hōrā et quadrante 7.15

Balneō māne an vesperī ūteris? Do you have a bath in the morning or the evening?

Plērumque māne. In soliō nōn sedeō, balneō Generally in the morning. I don't sit in the bathtub but have a

plūviō ūtor. shower.

Quotā hōrā ientāculum sūmis? What time do you have breakfast?

Octāvā hōrā At eight o’clock.

Quid edis? What do you eat?

Pānem tostum /frūctūs/ ova frīcta et Toast/fruit/fried eggs and bacon/cereals

lardum/cereālia

Quid bibis? What do you have to drink?

Theam/caffeam/lac/aurantiī succum Tea/coffee/milk/orange juice

Quotā hōrā ad officīnam proficisceris? What time do you leave for work?

Octāvā hōrā et dōdrante At 8.45

Domī labōrō. I work at home

Nōn est hōra cōnstitūta There's no fixed time.

Quantō temporis ad officīnam pervenīs? How long does it take you to get to work?

Quinquaginta minūtīs Fifty minutes.

Iter quamdiu terit? How long does the journey take?

Dimidiam hōram Half an hour

Quōmodo iter facis? How do you travel?

Autoraedā/Raedā longā/Tramine/Currū I go by car/bus/train/tram and then walk

ēlectricō vehor deinde ambulō.

Birotā ūtor. I use a bike

Ubi prandium sūmis? Where do you have lunch

In caupōnā prope officīnam/universitātem In a restaurant near my work/university

Quid edis? What do you eat?

Pastillum fartum/Collӯram/Iūs collӯricum/ A sandwich/noodles/soup noodles/rice/dim sum

Orӯzam/Cuppēdiolās

Quotā horā ab officīnā proficisceris? What time do you leave work?

Sextā hōrā et dimidiā At 6.30

Vesperī quid facis? What do you do in the evening?

Cēnam coquō (ancillam nōn habeō) deinde I cook dinner (I don’t have a maid), then watch TV or read a

tēlevīsiōnem spectō vel librum legō. a book. Sometimes I dust the furniture or do other

interdum suppelectilem detergeō vel housework. I also have to make the bed because there’s not

aliās operās domesticās facio. Lectum time for that in the morning.

quoque sternere dēbeō quod māne tempus

nōn sufficit

Quid edis vesperī? What do you eat in the evening?

Varium est. Saepe būbulam vel porcīnam It varies. I often have roast beef or pork with fried potatoes

assam ūnā cum solānīs frīctīs et holeribus and vegetables. Usually I drink beer or wine.

edō. Plērumque cervisiam vel vīnum bibō.

Domī furculā cultellōque an bacillīs ūteris? Do you use a knife and fork or chopsticks at home?

Sī orӯzam vel collӯram edō, bacillīs, If I’m having rice or noodles I use chopsticks, if it’s

sī cibum occidentālem, cultellō et furculā. Western food, a knife and fork.

Quandō cubitum īs? When do you go to bed?

Inter hōrās ūndecimam et duodecimam. Between 11 and 12. I normally listen to the radio before I

Soleō antequam dormiam, radiophōnum go to sleep

audīre,

Dē litterīs Latīnīs recitātiō

Quī scrīptōrēs Latīnī tibi maximē placent? Which Latin authors do you like best?

Inter scrīptōrēs classicōs mihi Ovidius Among the classical authors I particularly like Ovid

praecipuē placet quod fābulās iūcundās because he tells attractive stories with elegance and

cum ēlegantiā et facētiīs nārrat et wit and has a good understanding of the psychology

psychologiam amantium bene intellegit of lovers.

Quid dē Vergiliō? What about Virgil?

Est nōbilitās quaedam in versibus illīus There’s a certain nobility in his poetry and most people

et librī priōrēs Aeneidos plērōsque alliciunt. find the first books of the Aeneid attractive.

Nihilōminus rēs quās scrīpsit interdum Still, what he wrote is sometimes rather boring, unless

satis taediōsae sunt, nisi lectōrem proelia the reader is very interested in battles and agriculture!

et agricultūra maximē tenent.

Nōnne versūs Catullī multōs iuvenēs dēlectant? Don’t many young people like the poetry of Catullus?

Rectē dīxistī. Dē gaudiō dolōreque amōris You’re right. He wrote with great opnness about the joy and

sine dissimulātiōne scrīpsit. Etiam (vel potius the pain of love. Even (or should that be `especially’!)

praecipuē!) carmina quae obscaena habērī the poems that could be considered obscene appeal to lots

possunt multīs lectōribus placent! of readers!

Sī discipulus rudīmenta linguae didicit, quae If a student has learned the basics of the language, what

opera prīmum legenda sunt? things should he or she read first?

Fortassē nōn opera classica sed librī Perhaps to start with they shouldn’t read classical works

simpliciōrēs in prīncipiō legendī sunt.Verbī but simpler books. For example, the Epitome of Roman

grātiā, Epitomē Historiae Rōmānae ab History by Eutropius or the Bible.

Eutrōpiō scrīpta vel Biblia Sacra.

Nōnne tū ipse Caesaris opera prīmum lēgistī? Didn’t you yourself read Caesar first?

Ōlim in multīs terrīs discipulī commentāriōs In many countries students used to read Caesar’s

Caesaris prīmum legēbant et nūper in commentaries first and recently in American schools parts

scholīs Americānīs partēs librī `Dē Bellō of `De Bello Gallico’ have been put on the syllabus for the

Gallicō’ in syllabō probātiōnis superiōris, quae higher examination they call AP (`Advanced

AP dīcitur, inclūsae sunt. Latīnitās Caesaris Placement’). Caesar’s Latin is certainly good and his

certissimē bona est et verba eius faciliōra language is easier to understand than that of Tacitus, Livy

intellectū sunt quam Tacitī, Liviī vel Sallustiī. or Sallust. Still, not everybody is interested in military

Historia militāris, tamen, nōn omnēs tenet. history.

Nōnne Latīnitās Cicerōnis est optima? Isn’t Cicero’s Latin the best?

Scrīptor eximius erat sed tirōnēs orātiōnēs He was an excellent writer but he’s difficult for beginners to

eius nōn facilē intellegunt. understand.

Quid dē scrīptōribus mediaevālibus vel What do you think about medieval or neo-Latin writers?

neo-Latīnīs putās?

Multī putant linguam mediaevālem faciliōrem Many people think the medieval language is easier because

esse quod syntaxis et vocābulā similiōra sunt because the syntax and vocabulary are more similar to the

linguīs Europaeīs hodiernīs. Exemplī grātiā, modern European language. For example, in the medieval

aevō mediaevālī ōrātiō oblīqua simplicior facta period indirect speech became simpler because instead of

est quia nōn accūsātīvus infīnītīvusque sed the accusative and infinitive they started using the

`quod’ coniūnctiō et clausula adhibēbantur. conjunction `quod’ plus a clause.

Dē Latīnitāte recentiōre nōndum dīxistī. You didn’t say anything about more recent Latin.

Liber `De viris illūstribus’, historia contracta The `De viris illustribus’ (`On Famous Men’), an abridged

reīpūblicae Rōmānae, quae saeculō decimō history of the Roman republic that was written in the

octāvō scrīpta est, ūsuī est eīs quī rudīmenta 18th century is useful for people who have just learned

grammaticae Latīnae nūper didicērunt. the basics of Latin grammar. Most worth reading,

Dignissimus tamen lectū est liber annō mīl- however, is the book published in the year 1884 by

lēsimō octingentēsimo quārtō ā Franciscō Francis Ritchie which is entitled `Fabulae Faciles' (Easy

Ritchie ēditus, c.t. `Fābulae Facilēs.’ Est Stories). There is a recent version of this work which

versiō recēns operis, quam praeparāvit et in was prepared and uploaded to the Internet by Geoffrey

Interrētī posuit Galfrīdus Steadman: Steadman

http://geoffreysteadman.com/ritchies-fabulae-faciles/

Necesse est lectōribus scīre omnēs figūrās It's necessary for readers to know all the forms of nouns

nōminum et tempora indicātīva verbōrum sed and verb tenses in the indicative but in the opening chapters

in prīmīs capitulīs nōn adhibentur modus sub- neither the subjunctive mood nor the ablative absolute not

iunctīvus neque ablātīvus absolūtus, neque reported speech are encountered. before he can begin

ōrātiō oblīqua. Discipulō, antequam legere reading, the student has to learn off a list of 150 of the

incipiat, ēdiscenda est index centum quīnquā- words that occur most frequently in the text. In the

gintā vocābulōrum frequentissimōrum. In main part of the book explanations of all the words which

parte prīncipālī librī pōnuntur textuī Latīnō are not included in the list, together with note on points of

adversae explicātiōnēs omnium verbōrum in grammar are placed on pages facing the Latin text. The

indice nōn inclūsōrum necnōn commentāriī stories included are those of Pereus, Hercules, Jason and

grammaticī. Nārrantūr fābulae dē Perseō, Ulysses. Ritchie intended students to read these first

Hercule, Iasone et Ulixe, quās Ritchie volēbat before embarking on their study of the writings of Julius

discipulōs, antequam Caesaris operibus Caesar.

studērent, prīmum legere,

Et dē Latīnitāte hodiernā? And contemporary Latin?

Omnibus suādeō ut Nūntiōs Latīnōs I’d encourage everyone to listen to and read `Nuntii

Helsinkiēnsēs in interrētī audiant et legant. Latini’ ( Latin News) from Helsinki.

Quī scrīptōrēs Latīnī tibi maximē placent? Which Latin authors do you like best?

Inter scrīptōrēs classicōs mihi Ovidius Among the classical authors I particularly like Ovid

praecipuē placet quod fābulās iūcundās because he tells attractive stories with elegance and

cum ēlegantiā et facētiīs nārrat et wit and has a good understanding of the psychology

psychologiam amantium bene intellegit of lovers.

Quid dē Vergiliō? What about Virgil?

Est nōbilitās quaedam in versibus illīus There’s a certain nobility in his poetry and most people

et librī priōrēs Aeneidos plērōsque alliciunt. find the first books of the Aeneid attractive.

Nihilōminus rēs quās scrīpsit interdum Still, what he wrote is sometimes rather boring, unless

satis taediōsae sunt, nisi lectōrem proelia the reader is very interested in battles and agriculture!

et agricultūra maximē tenent.

Nōnne versūs Catullī multōs iuvenēs dēlectant? Don’t many young people like the poetry of Catullus?

Rectē dīxistī. Dē gaudiō dolōreque amōris You’re right. He wrote with great opnness about the joy and

sine dissimulātiōne scrīpsit. Etiam (vel potius the pain of love. Even (or should that be `especially’!)

praecipuē!) carmina quae obscaena habērī the poems that could be considered obscene appeal to lots

possunt multīs lectōribus placent! of readers!

Sī discipulus rudīmenta linguae didicit, quae If a student has learned the basics of the language, what

opera prīmum legenda sunt? things should he or she read first?

Fortassē nōn opera classica sed librī Perhaps to start with they shouldn’t read classical works

simpliciōrēs in prīncipiō legendī sunt.Verbī but simpler books. For example, the Epitome of Roman

grātiā, Epitomē Historiae Rōmānae ab History by Eutropius or the Bible.

Eutrōpiō scrīpta vel Biblia Sacra.

Nōnne tū ipse Caesaris opera prīmum lēgistī? Didn’t you yourself read Caesar first?

Ōlim in multīs terrīs discipulī commentāriōs In many countries students used to read Caesar’s

Caesaris prīmum legēbant et nūper in commentaries first and recently in American schools parts

scholīs Americānīs partēs librī `Dē Bellō of `De Bello Gallico’ have been put on the syllabus for the

Gallicō’ in syllabō probātiōnis superiōris, quae higher examination they call AP (`Advanced

AP dīcitur, inclūsae sunt. Latīnitās Caesaris Placement’). Caesar’s Latin is certainly good and his

certissimē bona est et verba eius faciliōra language is easier to understand than that of Tacitus, Livy

intellectū sunt quam Tacitī, Liviī vel Sallustiī. or Sallust. Still, not everybody is interested in military

Historia militāris, tamen, nōn omnēs tenet. history.

Nōnne Latīnitās Cicerōnis est optima? Isn’t Cicero’s Latin the best?

Scrīptor eximius erat sed tirōnēs orātiōnēs He was an excellent writer but he’s difficult for beginners to

eius nōn facilē intellegunt. understand.

Quid dē scrīptōribus mediaevālibus vel What do you think about medieval or neo-Latin writers?

neo-Latīnīs putās?

Multī putant linguam mediaevālem faciliōrem Many people think the medieval language is easier because

esse quod syntaxis et vocābulā similiōra sunt because the syntax and vocabulary are more similar to the

linguīs Europaeīs hodiernīs. Exemplī grātiā, modern European language. For example, in the medieval

aevō mediaevālī ōrātiō oblīqua simplicior facta period indirect speech became simpler because instead of

est quia nōn accūsātīvus infīnītīvusque sed the accusative and infinitive they started using the

`quod’ coniūnctiō et clausula adhibēbantur. conjunction `quod’ plus a clause.

Dē Latīnitāte recentiōre nōndum dīxistī. You didn’t say anything about more recent Latin.

Liber `De viris illūstribus’, historia contracta The `De viris illustribus’ (`On Famous Men’), an abridged

reīpūblicae Rōmānae, quae saeculō decimō history of the Roman republic that was written in the

octāvō scrīpta est, ūsuī est eīs quī rudīmenta 18th century is useful for people who have just learned

grammaticae Latīnae nūper didicērunt. the basics of Latin grammar. Most worth reading,

Dignissimus tamen lectū est liber annō mīl- however, is the book published in the year 1884 by

lēsimō octingentēsimo quārtō ā Franciscō Francis Ritchie which is entitled `Fabulae Faciles' (Easy

Ritchie ēditus, c.t. `Fābulae Facilēs.’ Est Stories). There is a recent version of this work which

versiō recēns operis, quam praeparāvit et in was prepared and uploaded to the Internet by Geoffrey

Interrētī posuit Galfrīdus Steadman: Steadman

http://geoffreysteadman.com/ritchies-fabulae-faciles/